We stayed albeit not without a few wobbles and so we experience yet another crisis through the eyes of a different culture. Once again the response has been typically chaotic but exceptionally moving. Currently, most people accept that Bangladesh is in an extremely vulnerable position when it comes to COVID19. On a national level, it is one of the most densely populated countries in the world, with over 160 million people living in a small area half the size of the UK. We have one of the lowest testing rates for coronavirus and social distancing is near impossible. Add into the mix, hundreds of thousands of migrant workers returning to the country in the last 2 months due to the global lockdown situation and a refugee camp for close to 1 million people and it is easy to see why no-one is quite sure of the current picture in relation to the precise extent of this devastating virus.

So, here are 5 things I have learnt about living away from my passport country during the turbulent times of the corona virus crisis

- Being ‘with’ people is harder when it impacts on your family

I’ll start with my own struggles. Many of our friends have agonised over a difficult decision to be either evacuated out by their embassy or stay and work. Most have gone. Watching from our roof as the evacuation planes fly over your apartment block is not for the faint hearted and brings all sorts of feelings of confusion and self-doubt. Questioning whether I am being a good father by keeping my children in a small apartment with no outdoor activities or walks, maneuvering 3 months of distance learning schooling with minimal resources and increasing their uncertainty about when they will ever get to see grandparents again is not a great feeling. I understand why people are leaving and a big part of me wishes I could be home, finding some security in our National Health Service but for me I believe The Salvation Army has an important role to play at this challenging time. So we stayed, helping to support the life giving emergency relief projects and life saving, essential medical services here. Only time will tell whether that was a wise decision or not but the act of being present with people is one thing we definitely signed up for. It feels important to be journeying together with the people we serve alongside right now but it is not without fluctuating emotions. We continue to pray that our faith remains stronger than our fears in the days ahead!

2. We are not all equal now but we do have things in common

I have seen and heard so many times that this crisis makes us all equal. It does not. We are not. Yes, it is indiscriminate and yes, we are all facing the same storms but this does not equate to a new found global equality. We are not all in the same boat! Even in Bangladesh, the corona virus does not make things equal between its anxious citizens and residents. I am able to selfishly stock up on food and medicine for a few weeks, while most people in Bangladesh are daily wage earners and struggle to live hand to mouth. I have ample space in my flat to isolate while less than a few metres away people are nervously couped up together with anywhere between 5 -10 living in a one roomed shack, sharing water and toilet facilities at risky public points. This crisis has also laid bare the poor state of health systems in some of the developing countries, where health insurance or state care are not even a remote possibility. However what emerges are beautiful commonalities of a wounded humanity in crisis. We all share kindness, strength and resilience as general societal and individual characteristics. Through this crisis, we have seen this all over the world. Kindness abounds across the country when it comes to generously sharing with others, no matter where you live. Sometimes it takes a disaster to bring out the strength in people or a population. Resilience is found in the least likely of places, unexpectedly reminding us that we all have a lot to learn from those who constantly bounce back from setbacks and crisis.

3. Fairtrade is not necessarily fair during times of crises

We are all connected, not just by handshakes or door handles but on a much more colossal scale. We have seen things from a unique perspective in Bangladesh and identified that in these connections, we see the best and worst in people. The best comes through the big-hearted support given by government, charities, businesses, individuals and for us, our supporting offices and territories. We have been enormously inspired by the selfless Salvation Army Officers, employees and volunteers in Bangladesh who, without any query or question, step up and step out to help the most vulnerable in their communities. But it also very difficult to sit and watch as many of the companies we use back home simply just cancel, put on hold orders or demand instant discount condemning millions of Bangladeshi garment works to be being sent home, unpaid and unemployed. I understand business is business but I can’t help thinking that it is easy to have good ethics and fair trade when things are going well but as soon as something goes wrong, once again the problem gets shifted down the line and ultimately it is the poorest who are the most vulnerable and hardest hit

4. Local solutions are possible

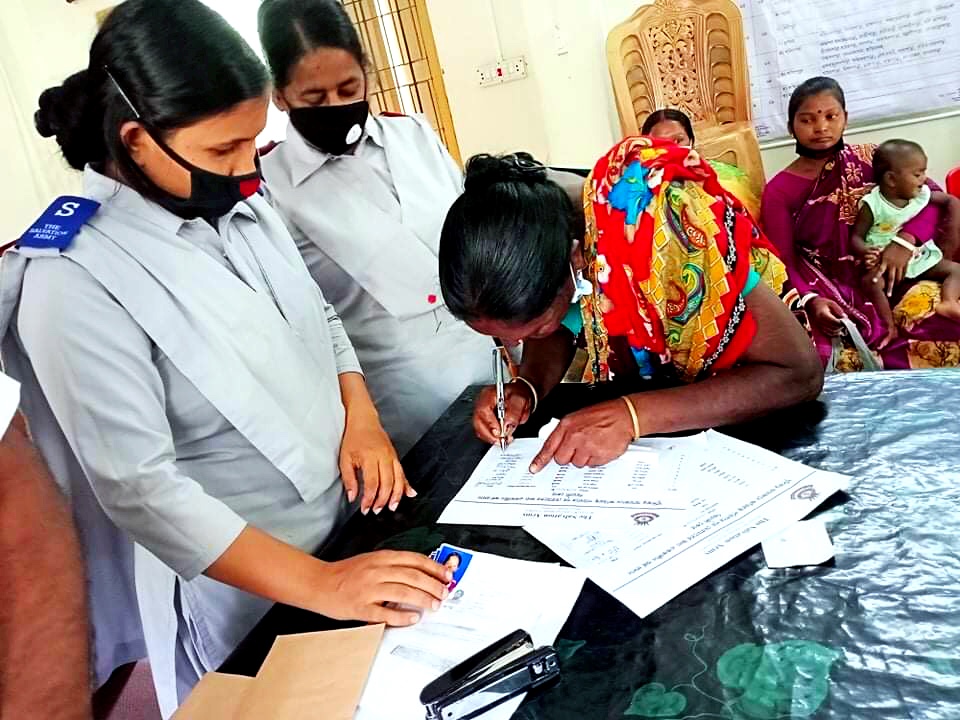

With a global scramble for equipment we are seeing local solutions emerging and the very best of the creative and innovative Bangladeshi minds coming to the fore. In the rural communities, the same inventiveness is on display when it comes to making your own soap or disinfectant and awareness raising activities. Bangladesh has a great history in implementing successful community based programmes in relation to family planning, TB and Leprosy and child illnesses (which TSA has been part of) and we can see this shining through again. The Salvation Army is present in communities and participates in the daily life of many of these innovative and creative approaches. It is resourceful and faithful people that inspire hope, that somehow manage to reassure us that everything might not turn out as bad as is being predicted. One leading NGO Executive Director puts it this way ‘while I am worried, I also have endless faith in Bangladesh’s ability to rise in a moment of crisis. Even when outsiders see us as a basket case, we see an innovative path forward’.

5. We need to unlearn and learn new ways of doing things

Our Strategic Plans, Mission Statements, budgets and logframes don’t prepare us for disasters, shocks or corona virus. They never have and never will. The developed world is understanding this more than ever right now but for most of the developing world, this is just the next in the line of disasters and shocks. In the midst of corona virus, Bangladesh is also preparing for dengue fever and monsoon season. My friend Matt White spoke really challenging words recently about how this a time when maybe we need to unlearn things while we have space to reflect; a sincere challenge for organisations as well as individuals. We can no longer just revert back to the way we used to do things, especially when that way largely benefits the agenda of the developed world. We need to find a new way and more flexible way of doing things that reflects the realities of life of those living in poverty, regardless of which country you live in.

Last night we watched The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel for our weekly movie night. One film commentator describes the film as being about ‘seven British retirees who travel to Jaipur, Rajisthan, India to live in a restored “luxury” hotel for the elderly. Predictably, their expectations are not met — the hotel is a shambles and its future in doubt — and just as predictably, the characters who take up the challenges thrown at them find a new, unexpected life’. It follows the idea of ‘outsourcing’ your older years to another country – it is especially poignant in a part of the world where our experience has been that people here have such a lovely and important respect for older people.

Last night we watched The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel for our weekly movie night. One film commentator describes the film as being about ‘seven British retirees who travel to Jaipur, Rajisthan, India to live in a restored “luxury” hotel for the elderly. Predictably, their expectations are not met — the hotel is a shambles and its future in doubt — and just as predictably, the characters who take up the challenges thrown at them find a new, unexpected life’. It follows the idea of ‘outsourcing’ your older years to another country – it is especially poignant in a part of the world where our experience has been that people here have such a lovely and important respect for older people.